CONGRESSMAN DAVY: Anne Royall, Playwright?

A pioneering journalist's "Theatrical Exhibition" in 1830s DC.

Anne Royall is at the center of Congressman Davy — the new musical I have written with Dean Schlabowske (Waco Brothers, Deano & Jo). While she is not the titular character, she is an engine of the work. The observer and explainer of our show.

Think of Royall as the Virgil of our 19th Century Washington DC Commedia. I omit the “Divina” on purpose. Anne Royall despised clergymen — and especially Presbyterians of her moment who stumped to erase the wall between church and state. (They didn’t like her much, either.)

Royall spent her life trying to explain America to itself. Her “Black Book” travelogues that focused attention on the diverse regions of the still-young United States were wildly popular in the 1820s and 1830s. The newspapers she published in “Washington City” — Paul Pry and The Huntress — opened up fascinating windows for me as a writer.

Yet that wasn’t all. Royall tried her hand at fiction in a novel called The Tennessean. And she wrote not one, but at least two, lost plays — one of which was a comic slice of White House humor that she self-produced at the height of the Jacksonian age.

I knew Anne Royall was an outsized American figure as I wrote the book and lyrics for Congressman Davy. What I didn’t know was that I had a sister of sorts as a dramatist.

Scandals of an Uncommon Scold

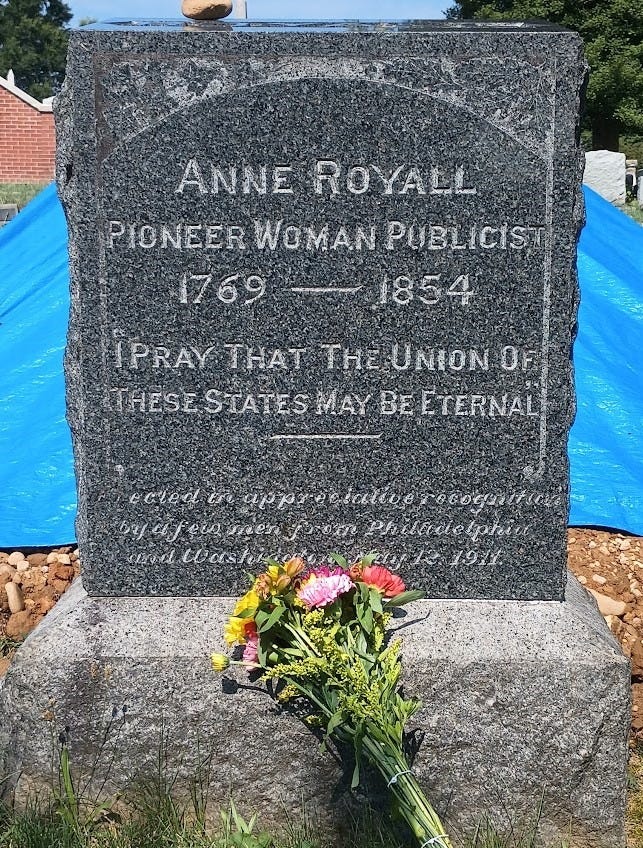

It is a tragedy of history that we do not have a portrait or photograph of Anne Royall. Indeed, detailed physical descriptions of her recorded by her contemporaries are almost nonexistent. Royall’s place in the public spotlight for over three decades certainly merited an image of some sort to cement her in public memory.

What we do obtain from her own writings — and the reactions of others — captures a woman as human whirlwind: strident voice, brusque manners, disheveled dress and an insistence on the importance of her own work in capturing her times with her pen. Royall traveled rough and alone from one end of the nation to another in the early-and-mid-19th Century to find material for her books, so she had to be resilient.

Her bold opinions and sharp pen won her snubs — and even assaults and beatings in some cities. They also were a precipitating factor in her infamous trial in 1829 in Washington City as a “common scold.” (She was found guilty but escaped punishment and found her public figure boosted by her courtroom appearance.)

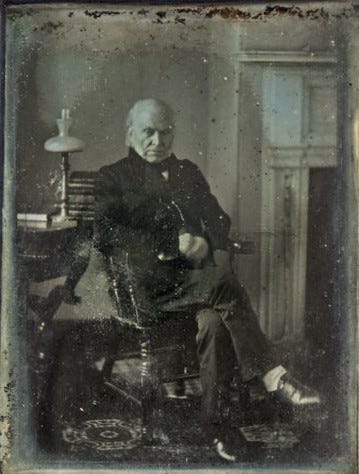

John Quincy Adams — the sixth President of the United States — perhaps captured Royall best in an 1827 diary entry penned during his administration:

Stripped of all her sex’s delicacy but unable to forfeit its privilege of gentle treatment from the other, she goes about like a virago errant in enchanted armour, and redeems herself from the cravings of indigence by the notoriety of her eccentricities, and the forced currency they give to her publications.

Royall was the widow of a Revolutionary War veteran named William Royall who was two decades older than she was. They met when she and her mother were employed as servants in his household, and the close relationship they enjoyed for years a number of years before their marriage in 1797 elicited gossip and contempt.

After her husband’s death, Royall became a pariah. Lawsuits by her spouse’s scandalized family stripped her of much of her just inheritance, and compelled her to pursue an lifelong quest to claim his military pension and survive under her own steam.

Scratching Out a Living With Her Pen

Painful exigency drove Royall to wander for many years — and eventually forged her career as a noted writer. Her first successes were trenchant and closely-observed travelogues that she began publishing in the 1820s.

As we have noted, a woman traveling alone in this era was at best seen as an “oddity.” At worst, Royall was subjected to vile abuse and afflicted by a persistent and treacherous poverty. Yet the “pen portraits” she drew of the era’s notable personages in her Black Books were gobbled up by enthusiastic readers eager to become acquainted with their fellow countrymen. Her books were found on desks of many legislators in the U.S. Congress.

Royall’s travelogues managed to amuse the public and annoy the locals in any region she visited. In short, she became a celebrity by sheer force of talent and will.

Yet by the late 1820s, the journeys grew wearying. She settled in what was then known as “Washington City” — a city that went boom-and-bust with the sittings and adjournments of the Congress. Political commentary (what we’d call “punditry” today) soon became the obsession of the two newspapers she published from 1831 until a few months before her death in 1854: Paul Pry and The Huntress.

Royall sold her latest edition every Saturday at the Library of Congress. But her papers never hit heights of circulation. Indeed, she often scrounged openly for “the needful” (aka “money”) in her newspaper columns — and even in person. Subscribers who failed to pay up were flayed in print. Royall was unabashed about the parlous circumstances in which she and Sally Stack (her longtime co-conspirator in journalism) were forced to labor.

In the pages of Paul Pry in the 1830s, Royall noted:

We sent SALLY to Philadelphia for a trifle to buy some paper with—(as for buying bread or meat, it is out of the question—we have to live on salt and potatoes.) ….

And after a pithy defense of exigent theft (below), Royall concluded:

Will our subscribers, near and remote, not help us? Surely they can divide with us. Were it not for our friends in this city, we should, ere this, have gone to the tomb of the Capulets.

Yet if Royall’s newspapers did not thrive, they did survive. And as I turned the pages of Paul Pry and the Huntress in the Library of Congress a few years ago, the words that she won with her resilience opened up a landscape of a young capital city that infiltrates every nook and cranny of Congressman Davy.

“Tickets $1,00. Proper officers will be appointed to preserve order.”

One of the startling surprises that awaited me in my research on Anne Royall is that she was a fellow playwright.

Perhaps it was no surprise that a talented and tenacious writer would turn her gaze to the theatre. Already, in 1827, she had published a novel titled The Tennessean. As Bessie James Rowland noted in her 1972 book, Anne Royall’s U.S.A., not only were reviewers unkind to the book, but they often omitted any mention of its merits to heap insults upon the author and debate her mental state.

Mr. Packard of Springfield, Massachusetts, readily picked up his abusive pen. He called Anne “a silly old hag,” and suggested that the place for her was “some asylum, or work house.” He got a prompt reply from, a New Hampshire editor. “We beg leave to inform Mr. Packard that there are different opinions … respecting the character of Mrs. Royall. Some of the editorial fraternity profess to regard with sincere respect that energy of mind, which has enabled her to overcome so many obstacles in her literary career.” The editor of a Connecticut newspaper was “convinced” that Mrs. Royall “is either an idiot or maniac; and in either case, she ought to be placed under the care of a keeper.”

Early in her book, Rowland also recounts that in 1824, Royall arrived on the dock in Georgetown from a winter spent in Alexandria, Virginia “without a penny in her pocket.” A draft of The Tennessean was in her bags, as well as “the draft of a play (she had never been inside a theater) …”

We never hear more about this particular work, but we know from her own 1826 book, Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States that she first tried to get a play onstage in Baltimore in 1823. Royall showed up to cajole the proprietors of Baltimore’s Holliday Street Theatre armed with a letter of introduction. (Rowland identifies them in her book as William Warren and William Burke Wood.)

As Royall made her pitch, she endured the sort of experience that almost every playwright has suffered through as they try to get a hearing for their work:

Having written some dramatic pieces while in Washington, I waited on Messrs. W. and W., proprietors of the theatre in this city …. The first of these … received me with a snarling growl, not unlike that of a surly, ill-natured dog, when another of his species enters his tenement ….

Royall had no better luck with Wood after suffering the bark and bite of Warren:

He was as polite and affable, as the other was vulgar and corrupt. He received me with an air worthy of Chesterfield himself, but when he understood that the piece I wished him to patronize was my own production, “oh,” said he, “that is out of the question, we play no American pieces at all, you must excuse me nor give yourself further trouble.”

Anne Royall did not give up her dreams of seeing a work on the stage. She had named her newspaper Paul Pry after the lead character of an English play which was popular in the 1820s.

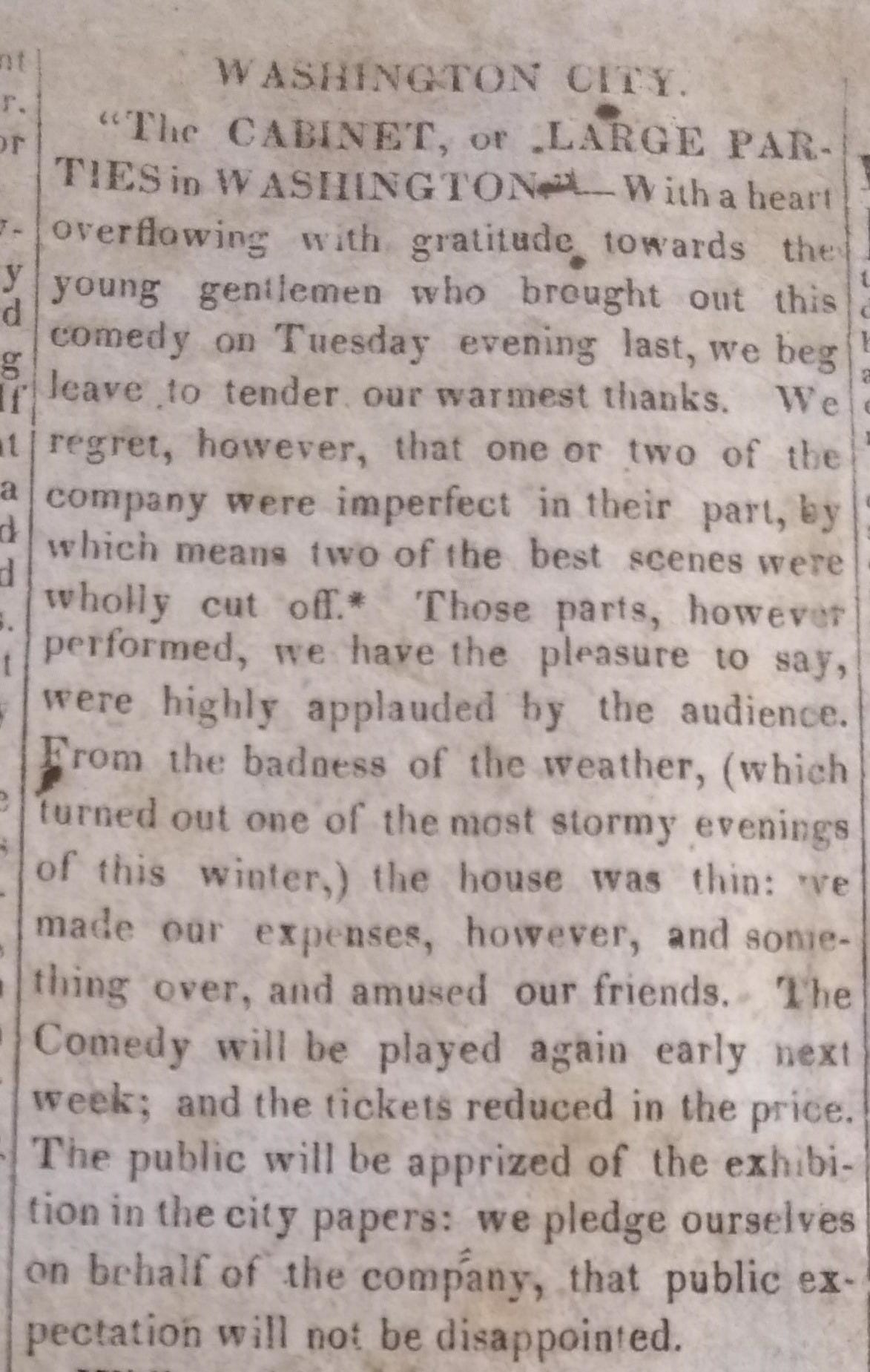

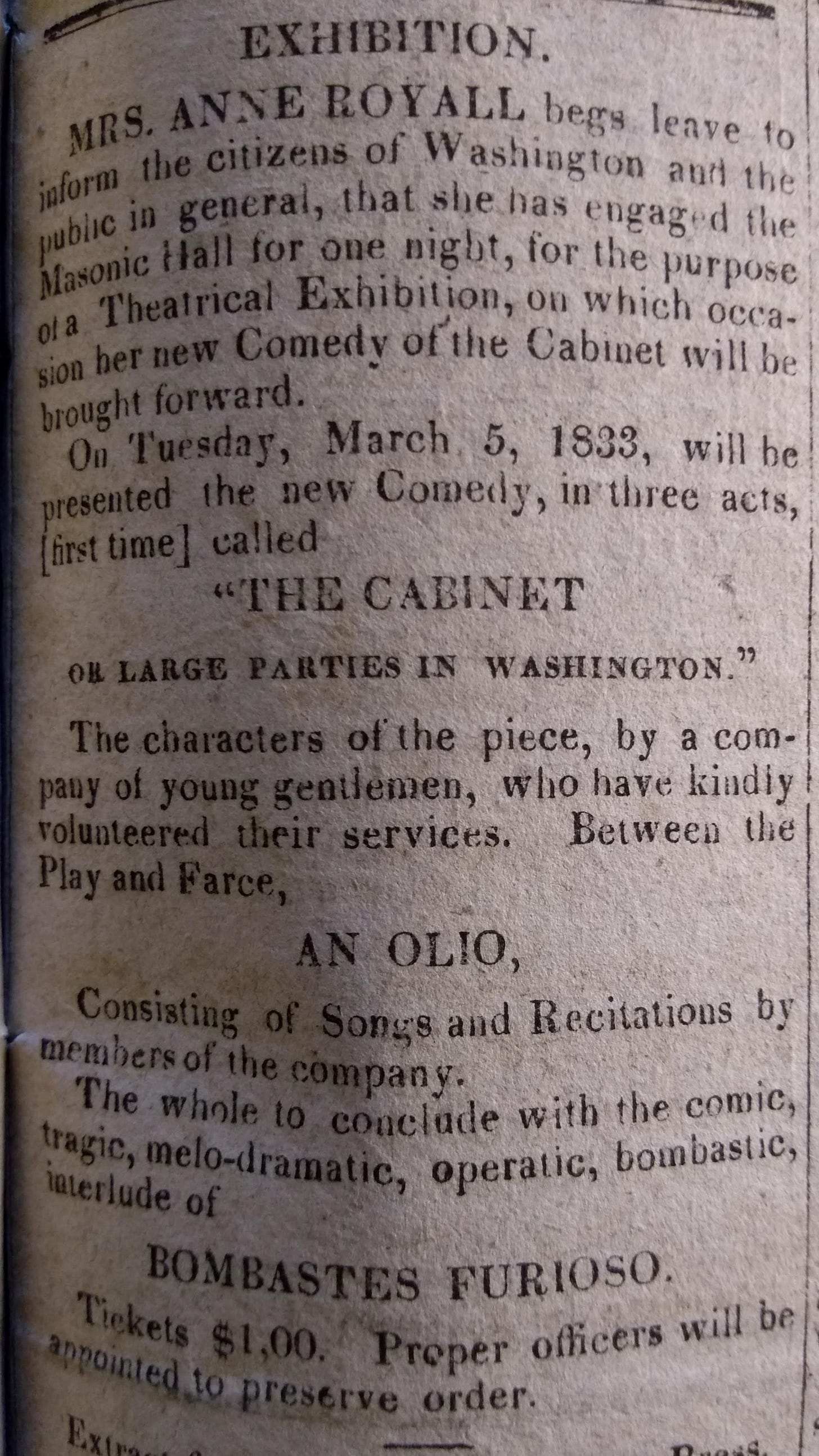

Finally, in 1833, Royall produced a new comedy — The Cabinet or Large Parties in Washington — in the nation’s capital. This play is also lost to history, but it was certainly a work that touched on President Andrew Jackson’s famous “Kitchen Cabinet” of advisors.

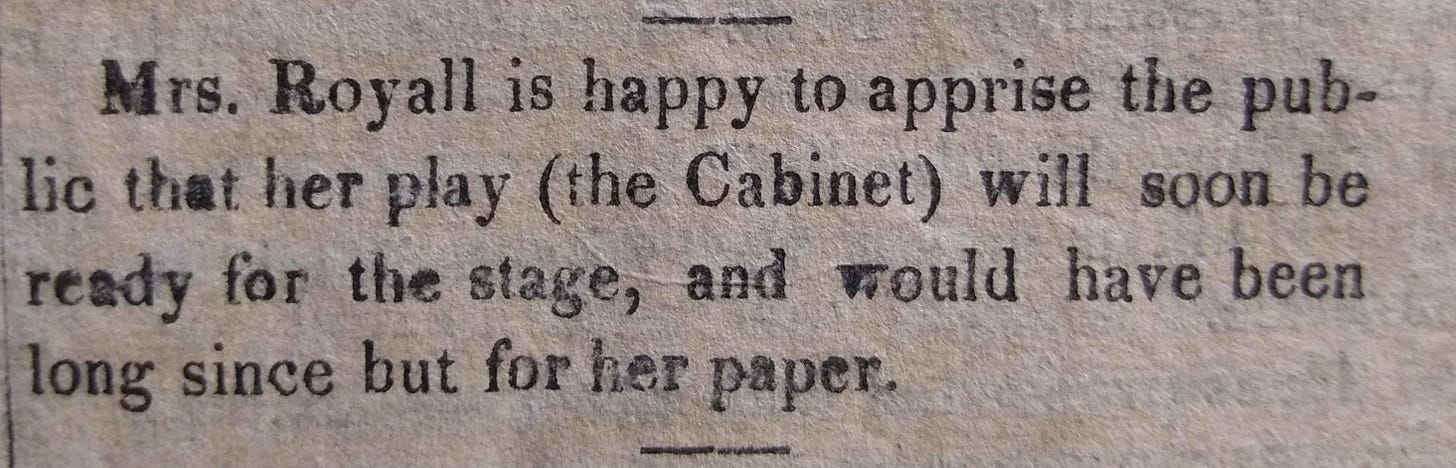

Royall had already published an apology of sorts for delays in getting the play to audiences, blaming the demands of journalism:

At last, on March 5, 1833, the players took the stage. She rented the Central Masonic Hall on D Street NW — a propitious location, since one of the two inaugural balls for President Jackson’s second inaugural had been held there the night before.

Royall laid out the full program in the pages of Paul Pry:

In Anne Royall’s U.S.A., Rowlands observes that the initial performance was a modest success that had a repeat performance a week later. Royall herself took the pages of Paul Pry to offer her thanks. Her words are best — and as playwrights are wont to do, Royall used some of them to point out deficiencies in the playing:

As Congressman Davy has its staged reading on November 1, 2024, I know as a playwright that I have a sister in Anne Royall. So many things have changed in Washington City over almost 200 years, but getting a hearing in our tumultuous capital remains a struggle that is worth the effort.