HOTEL MAYFLOWER: Tracing Toller's Steps

Dramatizing the life and work of a largely forgotten tragic hero.

Get my new book from Moloko Print — Hotel Mayflower — at Sea Urchin Editions.

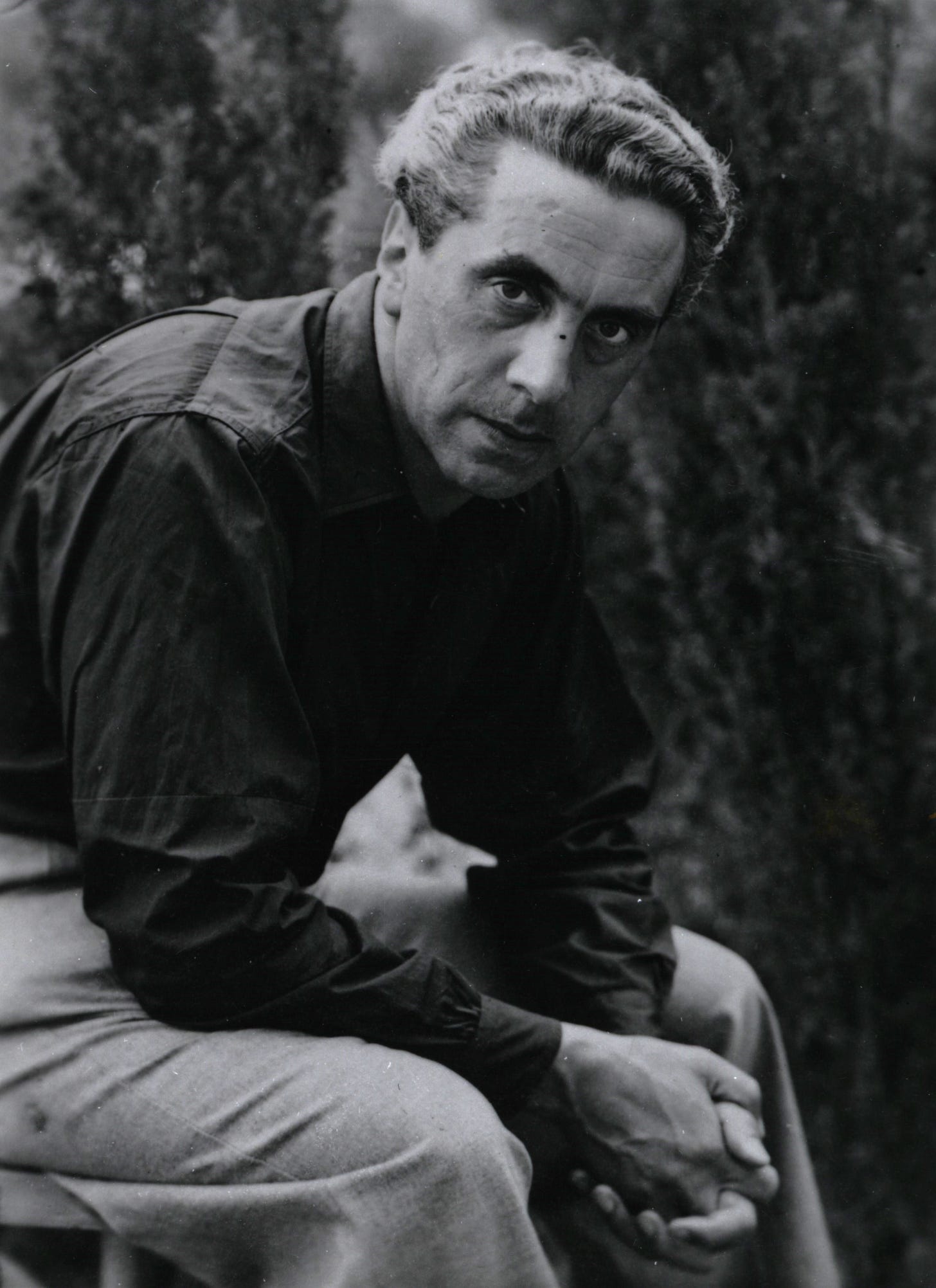

Eighty-five years ago today, on May 28, 1939, Ernst Toller was cremated at the Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum in Westchester County — just north of New York City.

In a letter dated June 15, 1939 (and published in English translation in 1998), exiled philosopher Ludwig Marcuse wrote to a fellow exile, writer Hermann Kesten, that “[t]he only ones present at T[oller’s] cremation were Toller’s cousin, myself, and an interested American journalist friend. The cousin asked me if it’s true that T[oller] used to give such expensive farewell gifts.”

A Sunday cremation attended by only three persons was a desolate epilogue to an extraordinary week. Toller’s tragic death by his own hand on May 22, 1939 made headlines around the world. Indeed, at the time of his death, George Bernard Shaw was the only living playwright more renowned than Toller.

Ernst Toller’s career played out upon a global stage, and he is an important figure in my play, Hotel Mayflower. The play offered me a chance to retell his story. It is a tale that is worth hearing as we grapple in our own time with resurgent fascism and political exile.

Toller was among the key leaders of the doomed Munich Worker’s Republic in 1919, and he survived its bloody end to become a symbol of that revolution’s continuing resonance. After being sentenced to five years for “high treason” in a highly-publicized trial, Toller wrote the poems and plays that secured his literary fame from his prison cell.

After he was freed from jail, his fame and penchant for activism made Toller a prominent target of the growing Nazi movement. When Hitler took power in 1933, he narrowly escaped arrest while traveling Switzerland and never returned to Germany. Toller only intensified his antifascist work in exile, giving lectures warning of the threat to democracy even as he became the first German Jewish exile to work as a screenwriter in Hollywood. (Numerous colleagues would follow him to work in Los Angeles in the late 1930s and 1940s.)

As news of Toller’s death spread, there was an immense shock in the left and center of global politics. Indeed, only the day before his cremation, hundreds of mourners had converged in Manhattan for Toller’s funeral at a prominent Broadway funeral home. So many members of the “who’s who” of New York City’s literary, theatrical, and political worlds sought a coveted invitation that the organizers actually ran out of the printed cards required for entry.

The speakers who eulogized Toller that day included Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis and former Prime Minister of the Spanish Republic Juan Negrín (who had been deposed in a coup d’etat in March 1939). Stella Adler read from Toller’s works. And various factions and parties battled over the right to place floral tributes at the playwright’s bier.

The lavish, crowded, and star-studded funeral stood in stark contrast to the three souls who gathered the next day at the crematorium. It was as if Toller had been forgotten literally overnight.

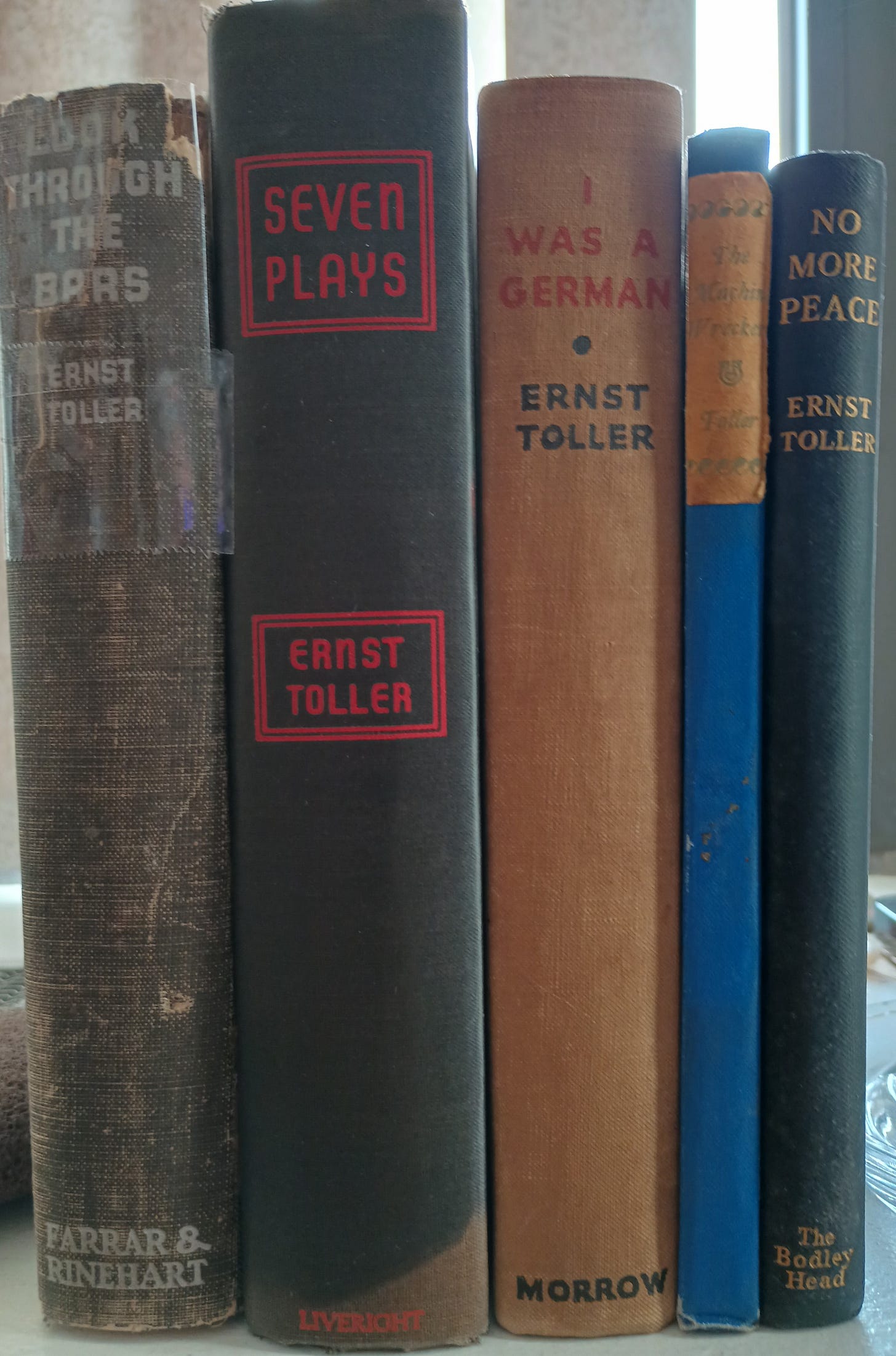

Toller’s literary reputation never really recovered after his death. His works vanished from stages. Even his powerful advocacy for a united front between left and center to fight the rising right embodied by the Axis powers also slipped away from public remembrance. Only three months after his death, on September 1, 1939, the fight that Toller warned about became an actual world war.

Yet retracing the story of Ernst Toller over the past ten years as I wrote my play, Hotel Mayflower, repaid my efforts to grapple with his life and work again and again. Revolutionary. Writer. Ferocious advocate for human rights and free expression. Why weren’t his life and works better known?

Accounts written by those who knew Toller immediately after his suicide focused on his final days, and the pressures exerted upon him by his failed marriage, an accelerating cycle of depression, and his increasing failure to adapt his work to the literary expectations of U.S. producers and audiences. Though his speeches and other public work as an antifascist activist were both influential and popular, Toller found it hard to write plays and poems in English. The translations of his works in the 1920s and 1930s soon became dated.

Posthumous remembrances of Toller also tended to focus on the least attractive elements of his personality: his grand ambitions, his penchant for performative gestures, and the disappointment of his expectations of continuing literary attention and acclaim.

As I dug deeper, however, I glimpsed a writer of extraordinary resilience and humanity. Toller’s enthusiasms were focused always on preserving human dignity and agency in a world that was increasingly dominated by foolish and destructive militarism and predatory capitalism. His spirit of solidarity led him to champion actions and alliances that would unite broad coalitions in defense of a free and humane society and culture, rather than irrational and useless political effusions.

In an essay from the late 1930s, for instance, Toller lays out the situation of his own moment in way that should resonate with anyone in 2024:

We are in the midst of an assault against the spirit, against human conscience. We have to make a decision. Generations and generations have fought for the spiritual freedom of man. Martyrs have suffered and died for that ideal. Today it is our duty to defend this most precious possession of mankind. A common front must be created where all those come together who are willing to defend civilization regardless of their different religious and political views. We may have different opinions, we may work for different political aims, but in this hour of deadly danger those differences are not important. We may go our different ways after we have succeeded together in securing the basis which alone makes life worth living: spiritual freedom and individual responsibility.

The action of Hotel Mayflower focuses on the last few months of Toller’s life. I fastened on this moment because it offered opportunities to juxtapose his views of the responsibility of the writer in society with William Burroughs’ beliefs — and examine the intersection of his own experience of exile with the journey of William’s wife, Ilse Herzfeld Klapper Burroughs.

Yet so much of my work on Hotel Mayflower involved working on weaving the totality of Toller’s life, work, and particular genius into my portrayal. One cannot ignore the tragedy of the closing years of Toller’s life, but any useful depiction of him in a dramatic work must dig deeper down into the roots of his experience and expression.

How was Toller shaped by the exaltations and failures of his brief moment leading a revolutionary movement? What effect did five years of imprisonment have on him? What was the interplay between Toller’s lofty ideals and innate pragmatism? How would a famous writer with a deep and pervasive empathy react to a desperate fellow exile like Ilse Burroughs — or a prickly and uncertain young man like William Burroughs?

At one point in the Hotel Mayflower, its characters discuss Toller’s narrow and fortuitous escape from the reactionary Freikorps forces that invaded Munich in May 1919 and ended its Worker’s Republic. The victors quickly executed many of the captured leaders of that government, including Eugen Leviné — a communist who seized power from the government led by Toller. At his pro forma trial, Leviné stated with blunt defiance that “we Communists are all dead men on leave.”

When William Burroughs asks why Toller did not seek out the martyrdom found by many of his fellow protagonists in the Worker’s Republic, it opened a window for me to weave the playwright’s past nightmares into his fraught present:

BURROUGHS: So you didn’t want to be a martyr?

ILSE: What sort of question is that?

TOLLER: A young man’s question. So I give the young man’s answer. The new government declared me dead. It was six days before they knew the mistake. I hid from the police for a month. (A sliver of a beat.) Every day, in my hiding place, I made the preparation for my death. But I was not tired of life. For me, the life was begun. I was glad to keep it – even in the prison.

Was Toller perfect? Far from it. Was he a tragic hero? I believe he was.

In 2020, I spoke with Ernst Toller Gesellschaft chairwoman Irene Zanol about Hotel Mayflower (when it was still titled Three Suitcases). In reply to one of her questions, I observed:

Perhaps the success of Ernst Toller is found not only in his achievements, but in his enduring example. To speak bravely. To strive for better. Always. We do not always need an Ernst Toller. But in our moment, we can learn so much from him. And we must. That’s why we retell the story. So it is remembered.