Get my new play Hotel Mayflower (Moloko Print) at Water Row or at Sea Urchin Editions.

When I decided to write Hotel Mayflower back in 2014, one of the key challenges I faced was how to portray William Burroughs as a 24 and 25-year-old man in the year 1939. (His February birthday falls between Scenes Two and Three of my play.)

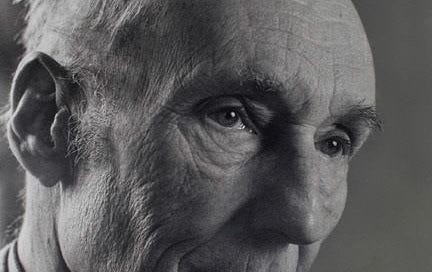

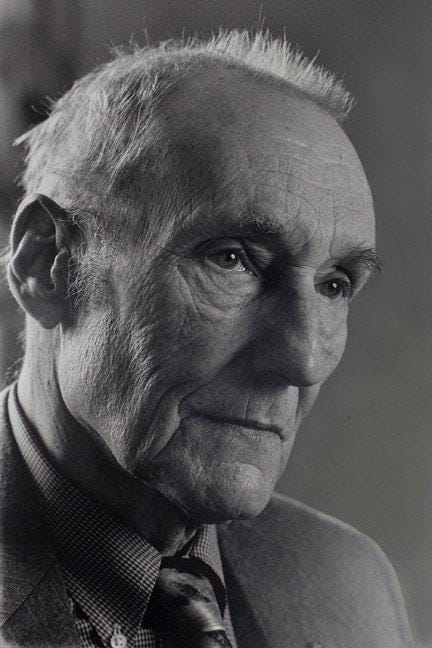

I met and interviewed Burroughs in 1989, so I had a vivid firsthand impression. Yet my meeting with him was almost precisely 50 years removed from the events of the play. That’s clearly not enough. What else did I need?

Part of the alchemy of playwriting is that you can summon up a compelling narrative from fragments and scraps. And that’s precisely what I had to work with between 2014 and 2018 as I wrote Hotel Mayflower.

Little if any written material from Burroughs exists in the public record from the years I was interested in tackling in Hotel Mayflower: 1937-1939. There also were no photos of Burroughs in those years. Indeed, since finishing the play, only one photo of Burroughs in that era has come to light: A photo taken in Dubrovnik with another young man in 1937, discovered by researcher Thomas Antonic and published in his book, Among Nazis: William Burroughs in Vienna 1936-1937 (Moloko Print, 2020).

The two full-length Burroughs biographies pay scant attention to these years and push on quickly. These curt accounts of 1937-1939 by Ted Morgan (Literary Outlaw) and Barry Miles (Call Me Burroughs) also are riddled with errors — some of which stem from an understandable reliance upon interviews given by Burroughs to Morgan (as well as to Victor Bockris for his 1981 book, With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker) long after these events occurred.

It’s hard to blame the biographers. As I discovered in writing Hotel Mayflower from 2014 to 2018, there was indeed precious little to work with to assist in the assembly of a reliable narrative. So relying upon a firsthand account from the man himself is tempting. Yet further investigation reveals that Burroughs’ memory often proves (suspiciously) selective and/or downright faulty.

As a playwright working from what I did know, I quickly surmised that these years were likely not a period of his life that Burroughs recalled with any fondness. He zig-zagged from graduate program to graduate program, clearly dependent upon the largesse of his family even as he began the explorations into underground culture (and even petty criminality) that would fuel his notable works of literature in later years.

Yet the lack of reliable archival material also proved to be a unique opportunity. Telling this story offered the chance to construct a narrative from the scraps, and engage with characters entangled in politics, exile, envy, trauma, and the act of being/becoming a notable writer.

So I read books that Burroughs certainly read, including Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West. I purchased books from the 1930s about Mayan culture, and re-read my Shakespeare. (Burroughs knew his plays and poems by heart.)

The earliest published letters we have from the Beat Generation icon are found in The Letters of William S. Burroughs, Vol. 1: 1945-1959 — six years removed from the end of the play. But this correspondence also proved useful. I focused a great amount of attention on the letters from between 1945 and 1950, noting down particular Burroughs turns of phrase and steeping myself in them.

The point was not to use any of these idioms verbatim. Too many years had passed. (I also soaked in a lot of American slang from the 1930s that would have been hanging in the air of every conversation.) What I wanted was to lay out for myself how Burroughs deployed such phrases — as well as create a map of sorts of the intricate play between his formal and colloquial speech.

Yet finding my own William Burroughs of 1939 was just the start. How did this young man interact with the other two characters in Hotel Mayflower?

Creating a workable and persuasive depiction of Burroughs’ relationship with his first wife, Ilse Herzfeld Klapper Burroughs, was largely a labor of imaginative sympathy (and empathy). They first met in 1936, when Burroughs was touring the region. When he returned to Dubrovnik to visit again in 1937 after surgery, he returned home to the United States as a married man — and wed to a woman who was 14 years older than he was.

Ilse’s motives were clear: She needed to escape from the dangers posed by the unpredictable politics of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the late 1930s. As a German Jewish expatriate in that country, her fear of deportation back to Nazi Germany was beyond legitimate. It was a near certainty.

Marriage to Burroughs was a clear escape route that would allow Ilse to leapfrog the immense backlog of quota-contingent visas to the United States. (And as Thomas Antonic and myself discovered later, Ilse’s divorce from her first husband was concluded shortly before her wedding to William.)

But why did William agree? In his interviews with Ted Morgan, Burroughs states clearly that Ilse cranked up the pressure on him to get married — and did so expertly. I hope you’ll read Hotel Mayflower to see how I wove this dynamic into a much larger narrative about Burroughs. Most of this work was trying to create a mosaic from scattered pieces of information about Ilse’s life, Burroughs’ childhood and early adulthood, and life in Dubrovnik in that moment.

Portraying the dynamic between William Burroughs and Ernst Toller offered even less in the way of hard information. Yet the conflict between their views of the role of artist in society is so stark and so immense that it proved inherently dramatic. The gap in their life experiences and overall engagement with the larger world also offered ample scope to the playwright.

Toller believed that the artist must address politics and society. Burroughs disagreed vehemently. The clash between them on this point is an engine of the play.

Yet the danger of the drama simply becoming a debating match was ever present. It seems clear from William’s thoughts on Toller that they did meet through Ilse, however briefly. So I spent a lot of time meditating upon what they might have thought of each other.

Reading deeply into Toller’s life and personality, he likely had immense respect and admiration for a young man who married a refugee to help her escape the Holocaust. I imagine he would have had a sort of affectionate indulgence for this prickly young Harvard graduate, now matter how irritating he might have been in that moment. Toller would have thought that Burroughs’ heart was in the right place.

Yet it seems clear that William harbored a dislike — even contempt — for Toller, rooted in his upbringing, evolving personality, and even envy. Indeed, for a young man with no significant accomplishments to his name, the career and fame of Toller must have incited both discontent and a searing sense of inferiority.

Some of these feelings also may have been suggested to him by Ilse’s attitudes. (William represents her feelings toward Toller as dismissive to the point of insulting.) But the animus on the part of future literary star toward a famed revolutionary, playwright and poet is clear in his subsequent utterances, even to the point of his tendency to distort and demean both Toller’s biography and achievements.

In short, there turned out to be a lot to work with for a playwright writing Hotel Mayflower — even in the absence of archival material to rely upon as I wrote. One could construct a believable Burroughs by researching and thinking and then writing into the biographical gaps.

But I invite you, the reader, to be the judge. I hope you’ll consider ordering a copy and exploring the world of 1939 yourself. You may find it startingly like our own.