In Search of Lola Montez

Can we discover the actual woman at the center of a radical transformation?

I recently came upon a startling image of Lola Montez that I had never seen before.

It is a drawing from 1855, taken from the notebook of an Australian artist John Michael Skipper, in the collection of the State Library of South Australia.

The image is called “In the ‘Green Room.’” It depicts Lola in costume, puffing a cigarette backstage. The taxing nature of her profession seems much in evidence here, even as she takes a moment away from the harsh light of the stage.

Is it an unguarded moment? Who knows? Did Lola Montez have many unguarded moments? But it is a very human moment. A peek behind the curtain.

Paintings and drawings of Lola that date from the most illustrious moments of her career — before the wider advent of photography — are highly stylized and suffused with glamor. (Even when, as I noted in a previous Stage Write essay, it is a rather sinister allure rendered by the brush of a hostile artist.)

The best-known photographs of Lola taken as the new technology swept into wider use do lack the actively-engaged sympathy of the portrait painter. Yet they tell us something different. Something equally fascinating and achingly real.

The earliest daguerreotypes of Lola show a woman playing to the crowds, and seeking out publicity and notoriety: hyping her costume for the famous “spider dance,” or provocatively holding a cigarette, or posing formally (and somewhat opportunistically) with a Native American chief who had visited the White House.

Later images of Lola — taken after her career as an actor and dancer ended — seem more calculated to elicit pity, or to put on record a sadness in her own circumstance and spirit. A later appearance of the shawl in which she performed, as well as her beloved pet dog. (Not in the public domain, sadly.) Or a number of the last photos of Lola that seem streaked with the grief of losing husbands and youth, and overshadowed by the looming illnesses which would soon not only disable her, but end her life in 1861.

Yet the dazzling array of images of Lola in any medium share something in common. They are, in the most essential way, performative. They seek to make an impression, or to capture some of the illumination which she radiated in a continuous fashion after her reinvention as Lola Montez. (And, most likely, even before that glorious and triumphant transformation.)

Which brings me back again to the backstage drawing of Lola Montez in Australia.

Gazing at it — and meditating upon it — exerted a certain magnetic effect, even years after I wrote An Evening with Lola Montez. It spoke so loudly to me about why I wrote the play, and what sort of effect I wanted to create as an author.

Until the crushing blow of her exile from the tumult of Bavaria in 1848, Lola was an icon. A dancer who aroused the fanaticism of the claques and the fury of her detractors, and swung repeatedly from triumphs to tragedies.

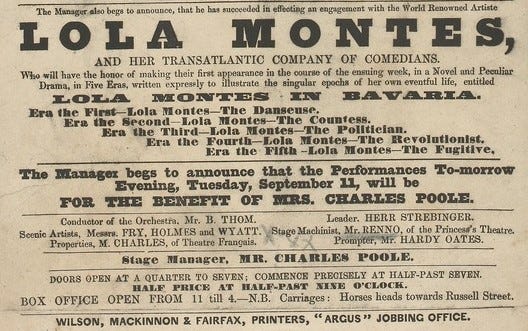

Cast into exile, with nothing but her talents and wits to deploy on her own behalf, Lola somehow managed to succeed in keeping poverty and ignominy at bay. Not only did she dance, but she also arrived somehow at a critical distance from “Lola Montez.” Perhaps her most popular role in the later 1840s and early 1850s was playing herself — as a character — in a play called Lola Montez in Bavaria. (Yes, very meta.)

Indeed, when I decided to write a one-act play about Lola — after she appeared fortuitously in another play I had written — the first thing that arrested me was reading an autobiographical lecture in which she gave the talk as someone other than Lola Montez:

The right of defining one's position seems to be a very sacred privilege in America, and I must avail myself of it, in entering upon the novel business of this lecture. Several leading and influential journals have more than once called for a lecture on Lola Montez, and as it is reasonably supposed that I am about as well acquainted with that " eccentric" individual (as the newspapers call her) as any lady in this country, the task of such an undertaking has fallen upon me.

It is not a pleasant duty for me to perform. For, however fearless, or if you please, however impudent I may be in asserting and maintaining my opinions and my rights, yet I must confess to a great deal of diffidence when I come to speak personally of one so nearly related to me as Lola Montez is. As Burns says, "we were girls together." The smiles and tears of our childhood, the joys and sorrows of our girlhood, and the riper and somewhat stormy events of womanhood, have all been shared with her. Therefore, you will perceive, that to speak of her, is the very next thing to speaking of myself.

Post-modernism, avant la lettre!

So what have I learned about this extraordinary woman from writing An Evening with Lola Montez? What might you discover if you encounter the play?

Hijacking Lola’s life and her legend to advance a particular aim or agenda is not unusual. Gossips and prudes have one version. Hedonists favor another. In the 1950s, even a celebrated filmmaker like Max Ophüls preferred using Lola to make larger points about art, sex and illusion over wrestling with the complexity of an actual person born as Eliza Gilbert in Limerick over 200 years ago.

The temptation always is to condense and simplify. But Lola left us something more valuable in her messy fractures and frissons: a portrait of what it means to be human in triumph and in tragedy.

There are no easy truths. And Lola Montez’s persistent flights from various truths of her own life — often in the pursuit of exigent self-preservation — make it even more vexing to ascertain them.

Yet my opportunity to inhabit Lola Montez’s complications and contradictions as a playwright gave me a sustained glimpse of her personal bravery. It is often expressed in a voice that that cuts clear through the fog of lies and shadows that make up her murky history — and our own.

So many times (as I write the play and ever since), I have heard that voice. It can lift our spirits and locate the aspirations that remain deep inside us. Lola tells us we can seize our own destinies. alter our trajectories, and reinvent ourselves. She calls upon us to be brave and to be human, despite it all.

Or as Lola says so eloquently in her introduction to a book of her lectures:

To all men and women of every land, who are not afraid of themselves, who trust so much in their own souls that they dare to stand up in the might of their own individuality, to meet the tidal currents of the world.