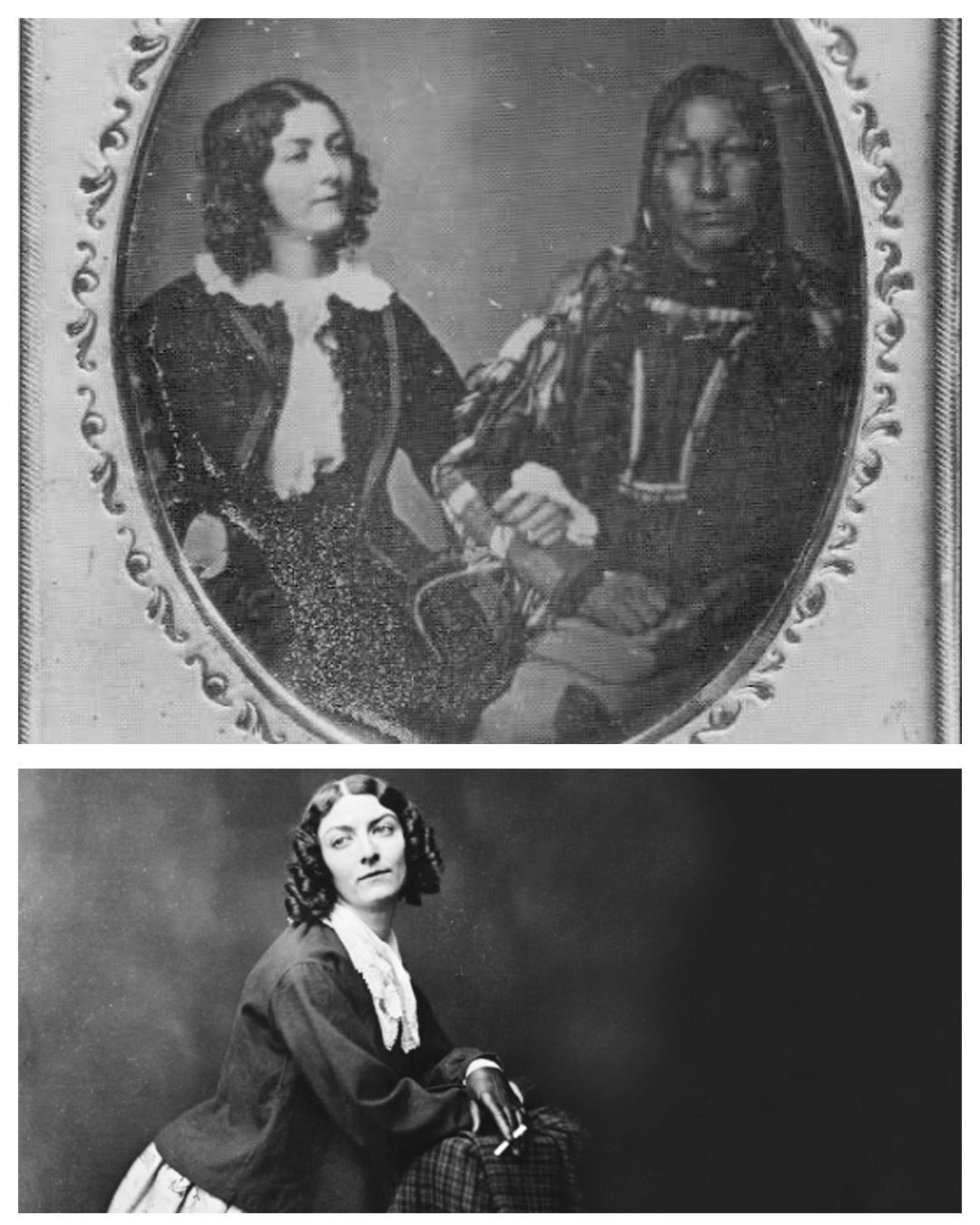

The photographs taken of dancer Lola Montez in the last decade of her life (1851-1861) are justly celebrated as groundbreaking. Among the images captured of perhaps the greatest celebrity of the mid-19th Century include the first photograph of a woman holding a cigarette, as well as the first daguerreotype of a woman with a Native American. (The latter photograph was taken in a Philadelphia studio in 1852, when Lola was snapped — however awkwardly — arm in arm with Arapaho chief Light in the Clouds.)

Yet photography had not yet advanced enough to capture the moment of Lola’s greatest celebrity in the 1840s, as she danced her way from England to Prussia to Poland to Bavaria (and many towns in between). It was a picaresque journey in which she would spark controversy, inspire claques, incite unrest, and even fan the flames of rebellion in that supremely revolutionary year of 1848, when the citizens of Munich compelled King Ludwig I to abdicate in part over a public liaison with Lola Montez.

History has had to settle for portraits of Lola painted in those years of her most luminous fame. And, of course, there were the caricatures that filled the pages of the popular press, promoting or pillorying the world-famous dancer according to the whims of both artist and audience.

One such caricature, from a book illustration, depicts a crowned Lola Montez as the imperious Countess of Landsfeld (misspelled “Mansfeldt” here), with King Ludwig I as her subservient lapdog on a leash. (Ludwig granted her the title in 1847.) She is depicted with a number of props — umbrella, knife, pistol — but most notably perhaps with a whip held precariously close to the royal head.

Another, and much later, caricature depicts a scrappy Lola Montez battling with an Australian journalist named Henry Erle Seekamp near the end of her career as a dancer in 1856. Seekamp had written a snidely moralistic and abusive notice of Lola as she toured the land Down Under that year.

Big mistake. Lola sought him out and thrashed him in a pub, reportedly using a whip to do so. Seekamp responded in kind with his own whip and his fists. They sued each other for libel and assault, respectively. The suits were later dropped. Yet there at Lola’s feet in the midst of the brawl is her riding crop.

So where did the association between Lola Montez and whips begin? Her stage performances certainly did not feature a riding crop.

Bruce Seymour, author of the extraordinary biography, Lola Montez: A Life, points to a strange but violent incident in Berlin early on in Lola’s dizzying rise to fame as a “talk of the town” dancer already performing at royal theatres.

At a military parade in 1843, Lola’s attempt to ride into the VIP section was met with firm resistance from a police officer, who grabbed the bridle and attempted to lead her back to the section reserved for the hoi polloi. Seymour continues:

The outraged [Lola] lashed out at the officer with her riding whip. He was incensed by the attack, but he had his hands full with trying to keep the crowd in order, so he left Lola in the spectator section.

Subsequently, Lola was served with a summons. Her reaction? Seymour says that her intemperate decision to rip up the document and stamp on the pieces led to a more serious charge of judicial contempt. And while her biographer adds that the record is unclear as to how the legal fracas was settled, reports of the incident in the press “turned into a gold mine of publicity for Lola” around the world.

In my play, An Evening with Lola Montez, the celebrated firebrand notes drily that:

Only once did Lola ever whip a man. True, it was a police officer.

Seymour adds that “it followed her the rest of her life.” It is a legend that has persisted — even to the present day.