Magick, Moogs, and Murder

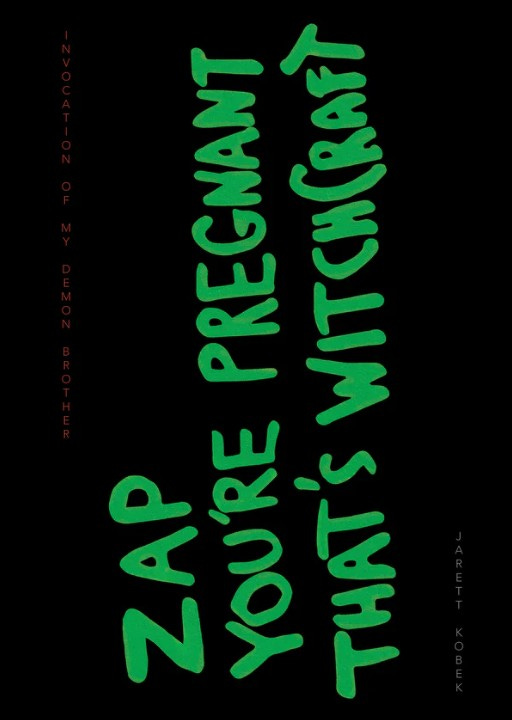

Jarett Kobek's new book weaves Kenneth Anger's film Invocation of My Demon Brother back into its distinctly Californian darkness.

As I plunged into Jarett Kobek’s extraordinary new book, Invocation of My Demon Brother (DieDieBooks), my thoughts turned to the Grateful Dead’s January 1969 appearance on Playboy After Dark.

This rare Dead TV gig of that era came to mind as I read because of a strangely awkward “interview” between Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner and guitarist Jerry Garcia that placed the contested landscape of Haight Ashbury squarely (ahem) between the two men:

HUGH HEFNER: Jerry, the Grateful Dead has been a part of the San Francisco scene for four or five years. Is the hippie scene changing now? I understand that ...

JERRY GARCIA: We're all big people now.

HEFNER: Certainly big in terms of publicity, etcetera. But I understand the Haight Ashbury scene has changed a good deal.

GARCIA: Well Haight Ashbury is ... just a place, you know. It's just a street. And it's not really the thing ... It never was the thing that was going on.

HEFNER: It was just the thing that got the publicity.

GARCIA: Right, right. That's the thing people could talk about because it's, like, easy to remember.

HEFNER: Well, they held, like, what, about a summer ago, they held a funeral for hippiedom ...

GARCIA: Right, right. And that was like, that was all of us saying, we're not going to tell anybody anymore what we're doing...

HEFNER: Start enjoying it again, huh?

GARCIA: Right, right.

Kobek’s Invocation for My Demon Brother shuttles deftly between the two evocative landscapes of 1960s California culture that collide in this conversation: the acid-saturated warped funhouse of Summer of Love San Francisco and hep industry town Los Angeles in the summer of 1969, when paranoia, perversion and violence bubbled furiously beneath the seemingly placid surface.

Our window into these vanished worlds is Kobek’s bravura take on the 1969 short film by iconoclastic and influential filmmaker Kenneth Anger’s that gives the book its title.

Invocation (the film) was shot in San Francisco in 1967 as flower power ferment melted in the heat of a national spotlight and congealed into one of the worst cultural trips on record. Anger’s movie was shown in Los Angeles at the Cinematheque 16 on October 10, 1969 at the precise moment when its star Bobby Beausoleil was already in a prison cell. He had been arrested for committing a murder that had instigated the carnage of the Tate/LaBianca murders only a few weeks before. (Invocation had screened already in London, New York and San Francisco in previous months.)

A key strand that runs through this story is how the dark and potent energies summoned by Anger’s filmmaking collided with the brazen follies of pop stars and their hangers-on who sought out squalid pleasures daubed with fire and madness. A few of them got burned — literally or reputationally. Others pirouetted away with a whiff of ash that intensified their celebrity. Some were doomed utterly by chance. Unlucky proximity. No Tarantino fantasia rescue.

Invocation is likely the smartest book you’ll read about film this year. A taut but snazzy account of the tangled rivalry between Anger and Andy Warhol. A fascinating new interview with Beausoleil about the film. Dazzling and tenacious forays into archives and yellowed clippings. Unlikely unturned stones long flipped over to reveal astounding new things. Plus, the residue of the author’s own encounters with Anger, which seeps into every page.

Yet Invocation is much more than the next classic book about cinema. Kobek’s work sails confidently into the place where fast, dark and cold currents of Californian violence and culture converge. It is territory its author knows well from many previous works: BTW, I Hate the Internet, and the double-barreled blast of Motor Spirit / How To Find Zodiac.

Passages such as this one sent my mind spinning to the Hefner/Garcia encounter:

The myths of 1960s California are fallacious.

Forget the Left Wing, the Maoists, the groovy vibes. It was a period and a place that served as a petri dish for every idea underlying a media-savvy Right Wing. Its p[participants were careless with themselves and other people. Driven by drugs. Minds ravaged. Things destroyed. Infantilism injected into the American project, forging a future in which every politician has a back catalog of YouTube videos. Where every prison warden’s dream is to spit bars om social media. Mommy blogger commits suicide. A world of deeply unserious people doing their thing.

Kobek acknowledges Invocation’s debt to William E. Jones’ incisive dive into the fascist iconography of Anger’s films — “He Brought A Swastika to the Summer of Love” — and calls this 2022 essay “[h]ighly recommended above all other writing on Anger.” Jones’ piece concludes by grappling with how precisely to assess the filmmaker’s pervasive reliance on Nazi and other pungent totalitarian images and source materials in our own moment:

Anger can be considered a visionary, his prescient films celebrating America’s death drive. Spectators find uncomplicated pleasure in them as long as no one looks too closely at their details, but as fascism advances at home and abroad, their iconography has become unavoidable. Calling attention to the swastika Anger brought to the Summer of Love is not necessarily a prelude to denouncing him as standing on the wrong side of history, but a way of emphasizing his relevance for today. Seen in this light, Kenneth Anger is not the artist who fulfills our most pious wishes, but the artist America deserves.

Three years on, of course, “not necessarily” may be carrying a bit more weight than it can reliably hold. Yet Jones’ central thrust is clear and irrefutable. Anger is ours whether we like him or not. He’s not going anywhere, man.

Perhaps this is why Invocation’s appearance in 2025 is so welcome. Jones’ essay is above all a pioneering work of “what”: identifying these images and fashioning a coherent map of their appearances in Anger’s films.

Kobek’s new book tackles two equally fascinating questions: “How?” “Why?”

With any and every element of Anger’s life story, such questions can remain astonishingly (and even flagrantly) “open.” The filmmaker was a prodigious liar, sorehead, and crank, lashing out at friends and foes with equal and often unhinged vigor. Even allegedly “informed” assessments fall short. Kobek observes that Bill Landis’ 1995 book Anger: The Unauthorized Biography of Kenneth Anger “is rife with blatant factual errors, often more than one per page….”

Thus, it has required dogged determination from the author simply to piece together how Anger filmed Invocation of My Demon Brother in two places 1n 1967: an architecturally over-the-top San Francisco mansion with a murkily unwieldy history near Alamo Square (the William Westerfeld House), and at a fraught performance at The Straight Theatre in the very heart of Haight-Ashbury.

And as the story moves out of Summer of Love and into the film’s uneasy and slightly serendipitous path to its Los Angeles premiere in 1969, Kobek’s task is no less daunting. That uneasiness was manufactured largely by Anger’s blustery and contradictory accusations of a theft of various reels of a larger project (Lucifer Rising) and his uncanny ability to alienate allies and antagonists. Indeed, Invocation of My Demon Brother is perhaps one of the great “self-contested” cinematic works of late 20th Century culture.

And the serendipities? Twofold. First, an alignment between Anger’s obsession with Aleister Crowleyan “magick” (forever with a “k”) and English pop-rockers’ increasing flirtation with similar materials allowed him to score a “soundtrack” created by Mick Jagger noodling on the trendy new Moog synthesizer of the moment.

The second bit of fate? The film’s central figure was a dreamy, complicated, and eventually murderous musician named Bobby Beausoleil — whose notoriety in the weeks surrounding the film’s release on October 10, 1969 grows apace. He is a key figure in the unfolding murder spree undertaken that summer by Charles Manson’s Family.

At the center of Invocation is a sublime frame-by-frame dissection of Anger’s film.

Yet this portion of the book literally fizzes with information that extends well past a mere description of what you are seeing. It boasts an explanatory energy that interrogates who you are seeing in this film (and their largely-curdled futures), Anger’s flagrant arcanities and flubs, and most important of all: how the flotsam and fuckups somehow coalesce into something utterly strange and compelling

In Kobek’s hands, laying out the how leads inevitable to the whys of Anger’s work. The filmmaker’s knack for plucking the highest string and openly piercing the most vulgar and unsightly boils. Recording the sound of it faithfully. Capturing what comes out.

A representative example offers the gist of how Kobek’s flashlight extends into every frame of the film:

[09:47] PROCESSION OF THE DAMNED PART THREE

Slightly advanced from the final moments of [09:46]. The second to last figure wears a papier-mâché black cat’s head and plays an instrument resembling a wooden speaking trumpet. Followed at last, by Beausoleil, wearing his top hat, hsi cape, and the same frilly shirt as in [02:31]. He wears the same pants as in Synder’s DO WHAT THOU WILT photograph. There’s no scorpion visible. Beausoleil plays a small, unidentifiable double-belled brass instrument. He lowers the instrument.

Charles Perry’s “Enigmas on Thin Ice: Dan Hicks Breaks Up His Hot Licks,” published in the 30 August 1973 Rolling Stone, contains this quote from Jaime Leopold:

[O]h, I was in the film Kenneth Anger made starring Bobby, Lucifer Rising. I was walked down a staircase wearing a crow’s head. An Anger trip, you know. everybody’s parading around in costumes. A raven’s head, it was.

Assume this memory is corrupted. But that it’s Leopold in the cat’s head.

Invocation’s most irresistible moments emerge as Kobek traces the twin journeys that bring Anger into confluence with Beausoleil, whom he envisioned as the “Lucifer” of a larger filmic project.

First, the two men converged in the saturated strangeness of 1967 San Francisco. A creepily-ornate mansion. Every band in town (including Beausoleil’s enigmatic and original Orkustra) knows they are gigging in the seed bed of the next big thing. Art is made. Tantrums are thrown. Shit is stolen. (Kobek’s efforts to sort out exactly what got lifted are herculean.)

Anger and Beausoleil both depart from the Haight long before the waves of Wolfe and Didion rolled in. Anger simply disappears. Buggers off to London. Eventually, the film in question takes shape from footage shot in that summer.

“Bobby splits,” writes Kobek. “He goes down to Los Angeles. Where he will take up with some vary unsavoury people.”

The second journey — in which Beausoleil and Anger come once again into uncanny (and, yes, even unsavoury) confluence is perhaps the most riveting part of Invocation.

Anger’s interlude in London somehow yields the almost 11-minute film at the center of the book. The filmmaker himself says it’s culled from discarded bits of a longer project: Lucifer Rising. A comprehensive debunking of this mythology is at the center of much of Kobek’s sleuthing.

Yet the London excursion also yields a miracle of transactional alchemy: Mick Jagger gets involved. He’s caught the film bug that will yield things sublime (Performance) and ridiculous (Ned Kelly).

Let Kobek explain :

Jagger records the soundtrack in November, 1968. On his own, in private, It can’t be called a demo. Subpar, junk, worthless. It’s not his music, his sound, his noise. It’s a patch done by The Man from Moog. Jagger has no intent. Noodling around with a new toy.

Almost a year later, Jagger needs Anger., Like Anger needs him. Jagger gives the track to Anger. But this is Jagger. London School of Economics rules. No one’s getting a free song. Not even two notes that he put together.

The soundtrack is old trash, someone else’s work with a bit of white noise and static.

But pair it with the mages.

And.

It works better than anyone could imagine.

Tempting as it is to quote at length from the book’s frenetic dash through the intersection of Anger’s film with the Tate/LaBianca murders, I will resist simply because you must read it yourself.

The factual record is clear. Anger’s back in California. Very late summer, if not autumn. He’s got something he managed to rescue from the shambles of 1967: Invocation. He’s starting to show it. At first, apparently, under a different title: Zap.

The Stones will play Los Angeles in November. Perfect publicity storm.

That storm soon becomes a hurricane. Bobby Beausoleil murders Gary Hinman on July 27, 1969 after an extended episode of torture over money that also involved Charles Manson and other members of the infamous Family. He’s arrested on August 7, 1969, sleeping in Hinman’s car.

The crime scene that Beausoleil leaves behind is a lurid diversion. Baffling bloodscrawl. He uses one of his jail phone calls to alert the Family. Cue the horrific Tate/LaBianca murders over the following two nights.

As Kobek points out, Invocation the film gets its first LA screening on October 10, 1969. It is the same day that the local constabulary starts to put the whole Manson case together and executes the first in a series of raids.

Such is Kobek’s mastery of the factual record that every interpretive leap he makes as he lays out the events between the August arrest and the film’s appearance at the crucial moment in Los Angeles sticks the landing.

How could a whole city know a thing that it couldn’t bring itself to say out loud? Inhabit an unspoken and yet deeply felt connection between art and violence? As Kobek observes: “If people say what they know, they’d have to say what they did.”

I also won’t spoil the ending. But let’s circle back to where we started, and why Invocation of My Demon Brother is such essential reading right now. This book lays bare the traffic between San Francisco and Los Angeles in this moment beyond the Electric Kool Aid and the slippery White Album cool, and beyond Jerry and Hef talking past each other. As Kobek observes:

Anger wanted vérité, the ultimate document of California.

A love vision.

Gets it in a way that no one could expect. Linked to the biggest crime story. Mentions in Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter. Included in every anecdotal biographical blurb. A mainline of the dark & primal, an infection that surfaces when the spirit is rotten and the flesh is willing.

Be careful for what you wish.