About six years ago, I wrote to Trevor Griffiths.

I wanted to tell him how much his plays and films meant to me. How much he had taught me as a writer.

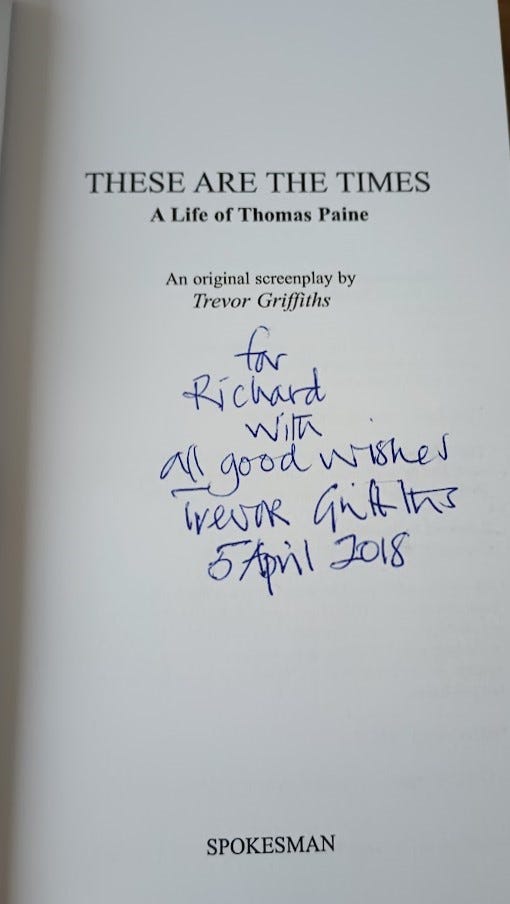

Griffiths wrote back, and he even sent me a signed copy of his extraordinary screenplay on the life of Thomas Paine: These Are the Times.

It was also the start of an epistolatory relationship – both with Trevor and with Gill, his wonderful wife — that was a boon to me throughout the pandemic.

Trevor passed away on Friday in Boston Spa, just a few days shy of his 89th birthday.

A few times in his writing, Trevor deployed a particular line of dialogue. It’s a good one. The version of it in The Party comes when a character says: “We only die when we fail to take root in others.”

Trevor Griffiths took root in our theatre and in our films — and in our moral and political moment.

As a model for how to write well (and especially about history), he also took root in me.

* * * * *

It’s hard to sum up a career that touched almost anyone who writes plays in English – even if they do not know it. Perhaps Griffiths’ most famous play is Comedians (1975) — which gave a brilliant young actor named Jonathan Pryce his first blast of fame.

Griffiths was the first dramatist to wrestle successfully with a play on the pain and pathos of stand-up comedy — and the ambitions of those who seek to work in that now-pervasive art form. He caught the essence of this enterprise so vividly that anyone who wrote about it afterwards owes him a debt.

Griffiths’ numerous other works for theatre and film also rank among the most important of our time. Occupations (1970) captures the eternal battle between optimism and pragmatism amongst revolutionaries through the lens of Italian communist Antonio Gramsci. The Party (1973) is perhaps the sharpest dissection of why progressive politics of any stripe smashes on the rocks of bourgeois intellectual imperatives. (It was also Laurence Olivier’s last role for the stage.)

Griffiths turned to television and film in the 1970s. Most notably, he scooped up an Oscar nomination for the screenplay to Reds (1981) — a film whose fraught production impacted everyone involved, including its screenwriter.

Yet for all the global reach of Reds, it is not Griffiths’ greatest writing for TV and film. Towering over everything in sheer scope and intensity is the 1976 series Bill Brand — in which Jack Shepherd plays the titular leftist Labour MP who battles ferociously against the conservative tides within his own party.

The series was dazzling in capturing its particular moment, but history also has been kind to Bill Brand. The core conflicts essayed in the series have continued to play themselves out in Blair’s New Labour and Kier Starmer’s more-recent Union Jack and Brexit-friendly refurbishment. If you want to know the streams in which Jeremy Corbyn swam as a young politician… watch Bill Brand. It is the finest television series about politics ever written and filmed. Riveting and human.

Trevor Griffiths was prolific. His miniseries on the South Pole race between Amundsen and Scott — The Last Place on Earth (original title Judgement Over the Dead) — transfixed me as a teenager when it was shown on television in the United States. There was also an exquisite adaptation of D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers — and encounters with Anton Chekhov that culminated in a terrific concentrated drama called Piano.

And so many other triumphs. Griffiths’ other major films for television in that era include the sublime Country (a 1981 TV film featuring James Fox in one of his greatest performances), the gloriously vivid Absolute Beginners from 1974 (with Patrick Stewart as Lenin), and Through the Night (1975)– a harrowing work that lays bare the terrors of battling cancer.

Arriving at our own moment, it is important to acknowledge that as a tide of new works on the life and achievements of Aneurin “Nye” Bevan is working its way to the screen, Trevor Griffiths was there first as well. His impressionistic biographical film on Bevan – Food for Ravens – stars Succession’s Brian Cox in the title role. It is a first-rate work: haunting, funny, and relentless in its portrayal of a man who sought social justice in how we care for each other when we are ill.

* * * * *

I want to finish my thoughts on a very sad day with why Griffiths matters so much to me as a writer.

There are times in the process of writing plays about history — as you amass immense amounts of research, and try to catch the substance and song of the past and why it matters now — when the writer feels alone. But my encounter with Trevor’s work left me feeling that someone had been on this road before and succeeded.

“I try to cover the ground,” he said once in an interview.

I try to find out the whole map of the ground that we’re dealing with. It might be about a 1945 upper class country house. It might be about a workingman’s club. But I spend a lot of time in places. I read a lot of books. I look at a lot of photographs. I make tapes. Interviews with people. I think the job, really, is to cover the ground enormously thoroughly, so that you really do appropriate it. You own that territory. You might use but a thousandth of the materials you’ve actually sought to master. But each piece that you use, each nugget that you use, will be connected, organically, to another hundred or another thousand pieces. It’s like a bed from which the text will grow.

I couldn’t describe my own writing process better than this. And to see Trevor say it so powerfully was startling to me at the time. And even now. It was like hearing someone say what I was doing out loud. It gave me courage to keep on.

There are a number of dazzling long monologues in The Party. Perhaps the most celebrated among them was delivered by Laurence Olivier in the original production. It is a searing indictment of the writer’s power to make actual change in the world.

This speech is given by Tagg – a Trotskyist who is mortally-ill, but still trying to accomplish the work of the revolution to his dying breath. He offers it to a gathering of trendy leftists gathered for drinks and conversation in a sympathetic film and theatre director’s home.

At one point, Tagg says:

You’re intellectuals. You’re frustrated by the ineffectual character of your opposition to the things you loathe. Your protest is verbal—it has to be: it wears itself out by repetition and leads you nowhere. Somehow you sense—and properly so—that for a protest to be effective, it must be rooted in the realities of social life, in the productive processes of a nation or a society. In 1919 London dockers went on strike and refused to load munitions for the White armies fighting the Russian Revolution. In 1944 dockers in Amsterdam refused to help the Nazis transport Jews to concentration camps. What can you do? You can’t strike and refuse to handle American cargoes until they get out of Vietnam. You’re outside the productive process. You have only the word. And you cannot make it the deed.

Later in the same monologue, Tagg turns the knife again, attacking not only the impotence of writers, but also a poverty of imagination in their political vision:

… Suddenly, you lost contact—not with ideas, not with abstractions, concepts, because they’re after all your stock-in-trade. You lose contact with the moral tap-roots of socialism. In an objective sense, you stop believing in a revolutionary perspective, in the possibility of a socialist society and the creation of socialist man. You see the difficulties, you see the complexity and the contradictions, and you settle for those as a sort of game you can play with each other. Finally, you learn to enjoy your pain; to need it, so you have nothing to offer your bourgeois peers but a sort of moral exhaustion. You can’t build socialism on fatigue, comrades. Shelley dreamed of man “sceptreless, free, uncircumscribed, equal, classless, tribeless and nationless, free from all worship and awe.” Trotsky foresaw the socialist man on a par with an Aristotle, a Goethe, a Marx, with still new peaks arising above those heights. Have you an image at all to offer? The question embarrasses you. You’ve contracted the disease you’re trying to cure.

Trevor Griffiths’ own life and works undermine the provocative and searing viewpoint he articulates through Tagg in The Party. His works did make tangible change – and they will do so as long as they are read, watched, and performed.

What’s more, Griffiths offers powerful images of human beings striving, collectivizing, and reaching beyond themselves to improve the society in which they live. These are powerful and indelible portraits that have taken root.

One of my favorites can be found in the rousing script for Griffiths’ unproduced teleplay, Such Impossibilities. This work is about a successful 1911 transit strike in Liverpool led by legendary trade union leader Tom Mann. The revenge of authorities came when Mann was arrested under the UK’s 1797 Incitement to Mutiny Act for his call to British soldiers not to fire upon strikers.

At the end of the play, Tom Mann’s wife Ellen Mann visits him in jail:

ELLEN: I’ll never understand, Tom.

MANN: No. I know.

ELLEN: Why you do what you do. It’s beyond me.

MANN: I … have to, love. You know that.

ELLEN: I know that.

(MANN closes with ELLEN, draws her in to him.)

MANN: You know, when they buried the Duke of Wellington, 1840 something, one hundred and twenty thousand people turned out for the funeral. They said then, no funeral could ever touch it, for size and scale and dignity. Forty years later I went to a worker’s funeral. Alfred Linnell he was called—a general labourer, killed by police in a demonstration in Hyde Park. The mourners at that funeral were estimated at one hundred and fifty thousand. For an unknown worker. In forty years. And we’re only just starting.

(ELLEN’s crying at his shoulder. He notices.)

MANN: Hey hey hey hey hey. You can’t be crying. I’ll not have you crying. The working class don’t cry, lass. We’ve nothing to cry for. We’re winning.

Purchase many essential works by Trevor Griffiths through Spokesman Books.