HOTEL MAYFLOWER: Imagining Ilse

Sifting scraps of evidence to find a fascinating woman at the center of the story.

Get a copy of Hotel Mayflower at Sea Urchin or Water Row Books or the Moloko Print shop.

In August 2020, two envelopes arrived at my door in the midst of the pandemic from the National Records Center. Inside them were images that I thought I might never see: two photographs of a playwright’s very elusive quarry.

These photocopies of immigration papers included two previously unseen images of Ilse Herzfeld Klapper Burroughs — the first wife of Beat Generation luminary William Burroughs — during the time of her marriage in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Some of Ilse Burroughs’ U.S. immigration documents were available online before 2017, but none of them contained a photo. So I requested records that I knew would have one: (a) her successful 1938 application for a coveted non-quota visa; and (b) her formal naturalization as a citizen in 1944.

(These images appeared first in September 2023 in an article which I co-authored with Thomas Antonic, a Beat Generation scholar whose book on William Burrough’s sojourn in Vienna in 1936 and 1937 — Among Nazis — broke important new ground in Beat studies.)

Back in August 2020, I was exhilarated to finally see the woman whose life I had dramatized in my play, Hotel Mayflower — however belatedly. The play had been finished in 2017. It was a semifinalist in a national playwriting competition in 2019, and had three successful public readings (including one at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan) before the COVID-19 pandemic took hold.

The publication of Hotel Mayflower in a bilingual edition (English/German) by Moloko Print in April 2024 led me to revisit how I set about creating a characterization of Ilse Burroughs from scant bits of available information.

I examined fragments and scraps of information to create a mosaic that was aligned with indisputable events in Ilse Burroughs’s life: her flight from Berlin after 1933, a need to escape deportation back to Nazi Germany in 1937, a serendipitous marriage to a man 14 years her junior that same year, and her arrival in New York City in the dead of winter in 1939 in search of a job.

I fastened on a few key items that helped me tell Ilse’s story as I wrote between 2015 and 2018: a few words from William Burroughs; a picture of a ship; an address; a signature; and a manuscript letter.

“A shrewd birdlike face … ”

The first place I sought information about Ilse Burroughs was in the two extant biographies of William Burroughs: Ted Morgan’s Literary Outlaw (1988) and Barry Miles’ Call Me Burroughs (2013). Both books rely heavily on material from Morgan’s interviews with Burroughs over four years to create his book. And as I have written elsewhere, Burroughs’ account is not always reliable. (Especially almost five decades years after the events in question.)

Yet William Burroughs and his biographers did provide some very crucial evidence with which one could start to shape a dramatic portrait.

First (and in the absence of a photograph): what did Ilse Burroughs look like? What was her manner?

In Literary Outlaw, Morgan paraphrases his interview with William Burroughs fairly directly: “Ilse was a small-boned woman of about thirty-five, with a shrewd birdlike face and brown eyes …. she was straightforward and slightly mannish and wore a monocle, and Billy liked her at once, liked her humor and her lack of pretense. She saw through every phony.”

This forthrightness and toughness was a key to Ilse’s character. And the physical description provided by Burroughs reminded me of one of the most famous of all the portraits of Weimar Germany: Otto Dix’s 1926 portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden (above).

Almost 50 years later, von Harden recalled that Dix stopped her in the street and insisted on doing a portrait: “You are representative of an entire epoch!”

Without an actual image of Ilse to ponder, Dix’s painting became somewhat talismanic for me as I wrote Hotel Mayflower.

A Winter Passage

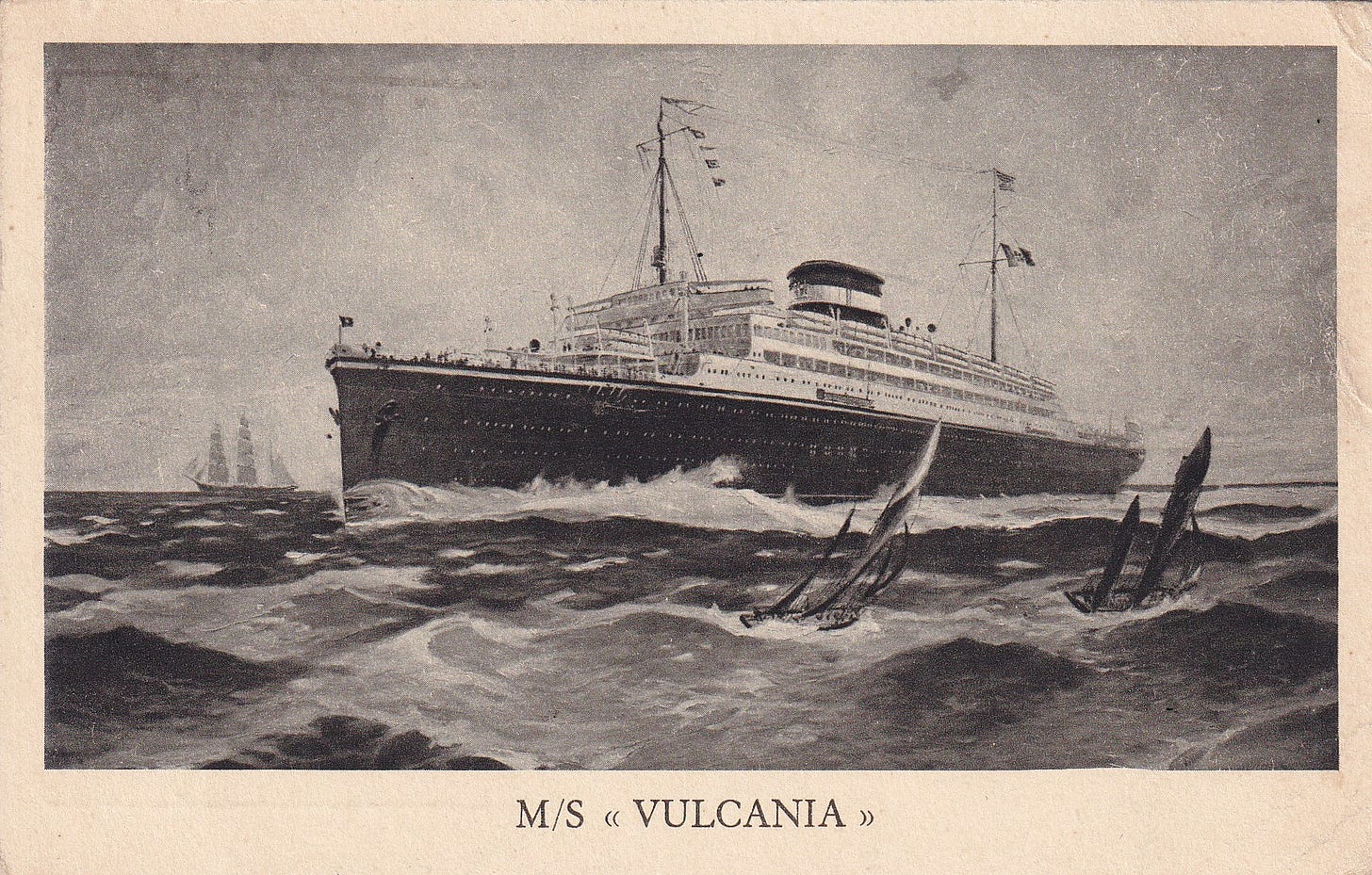

Other immigration papers that I had as I wrote the play included more key information about Ilse Burroughs’ journey to the United States, and her arrival in New York City on January 19, 1939 on the MS Vulcania.

The boat’s manifest of “alien passengers” was a gold mine. Her ship left Dubrovnik on January 5, 1939. She was still using the name of her previous marriage (“Klapper”) as a middle name. She listed being a speaker of three languages. Her “race or people” was “Hebrew.” Her profession was “h.wife.”

Yet things past mere biographical detail leapt out at me. Ilse Burroughs did not wait until spring and better weather to leave Yugoslavia. She endured a winter passage across the Atlantic Ocean to escape. Her urgency was apparent, especially considering that her non-quota visa was issued in Zagreb in early December 1938.

Dig deeper — and Ilse Burroughs’ trip to Zagreb sticks out even more. The distance between Zagreb and Ilse’s home in Dubrovnik is large: 372 miles. In 2024, it takes six hours’ drive in the best conditions. Railway maps suggest something even more arduous. There are no direct trains at all between the cities. Ilse would likely have had to take a ferry north to Istria to travel on a railroad running from Rijeka to Zagreb via Karlovac.

Put simply: This was a long trip to undertake in 1938. It is a journey that one takes when one is desperate — and determined to take full advantage of the good fortune she had in marrying William Burroughs.

I also took serious pains to investigate what a journey on the MS Vulcania in any weather might have been like in 1939. I dove into the ship’s history. Menus of the meals served on board. I even found a YouTube video of a trip on the ship taken in 1938.

At one point, I located a postcard of the MS Vulcania from that era — and made it part of my collection. It was all a part of trying to imagine myself into Ilse’s experience of flight from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

A Walk Through the Park

Ilse’s application for naturalization was also available as I wrote Hotel Mayflower_—and this 1942 document was a gold mine. It contains personal details: the brown eyes that Burroughs remembered, and a height of five feet, three inches. It also shows that she still uses her former married name as a middle name. Her profession is now “secretary.”

Another thing that caught my eye was her address: 230 E. 61st Street, New York, NY.

Some newspaper accounts of Ernst Toller’s suicide published in May 1939 that name Ilse Burroughs as the person who found his body mix up “West” with “East” in her address. But her apartment in 1939 — and for a number of years thereafter — was on East 61st Street.

When I went to visit that address in 2017, I found a much restored building — but indubitably still the one in which Ilse lived. Yet I wanted to get a sense of her own landscape of 1939. So I decided to walk to work at the Hotel Mayflower with Ilse.

Ilse’s apartment was on the other side of Central Park from Toller’s room at the hotel. And there is no easy shortcut across the park. Going through Central Park means skirting The Pond in its southeast corner and emerging eventually on its west side, just a few blocks north of the Hotel Mayflower.

Ilse also could have walked down to 59th Street along the southern edge of the park, and then around Columbus Circle and two blocks up to the Hotel Mayflower. She would have passed the monument to those who dies in the explosion of the USS Maine in 1898 every day on that route.

Both paths take about 30 minutes. But walking them left me feeling a bit closer to Ilse and her daily routine in the months after landing as an exile in the big city.

“A key to unlock a door …”

Ilse Burroughs divorced William Burroughs in 1946. Yet she never gave up the name “Ilse Burroughs” to revert to “Ilse Herzfeld” or “Ilse Klapper.”

As I wrote Hotel Mayflower, it was frustratingly easy to track her travels to Europe and back in the 1940s and 1950s and 1960s using the name “Ilse Burroughs.” I wanted to know more about her youth and young adulthood and marriage — and not the vacations she took after her divorce.

In the moments when I felt that I couldn’t find enough about her, my mind would wander to the question of her name. Why didn’t she change it? I would gaze at her various signatures on documents and wonder about it.

Eventually, these musings spilled into the play itself. At one point, as Ilse and Ernst Toller discuss their exile experiences and the suffering inflicted by the journeys they have taken, she tells him:

I feel I have lost everything but my names. I have so many now. Herzfeld at birth. Klapper. Now, Burroughs. When I write “Burroughs” on a form, the name looks like a key to unlock a door. (A half beat.) Elsie Burroughs is a name to hide in. (A beat.) I am lucky to have it. No one wants a Herzfeld here. Or a Klapper. We are a problem now. And thousands just behind us. (A half beat.) Am I still a human being? Not here. I am a long string of names. (A sliver of a beat.) I know should be grateful. Burroughs is a name that saved my life. But I live in this name now, and I wonder: “What for?”

“I am sorry I can&t be of more help …”

The most important day of the entire journey of writing Hotel Mayflower was May 10, 2017. That was the day I went to Philadelphia to meet with the renowned Ernst Toller scholar John Spalek.

Spalek was not in the best health, but we talked at length about Toller. Near the end of my visit, he asked me: “What would you like to see?”

I was in shock. I didn’t know he had any research materials in his apartment. He took me back into a room with some file cabinets. The first thing he showed me was startling: a letter to him from Ilse Burroughs from 1965, typed on onion skin paper and signed: “Sincerely I Burroughs.”

Indeed, my surprise was so immense that when Spalek urged me to take a photo of the letter, I botched it not once but twice with my tablet. (Fortunately, the flash spot at the center of the letter was different each time, and the text of the full letter was available to me from combining both images.)

I had about 40 minutes left before I needed to go, but he left me alone with the files of Toller’s correspondence he had kept. I plunged directly into two years: 1933 and 1939.

So much of my effort was educated guesswork. Hunches. This was a chance to confirm (or abandon) them.

In 1933, I found a letter that was typed by Ilse for Toller during his time in Dubrovnik after the famous PEN conference in May of that year, when he spoke bravely and boldly against the Nazis attacks on writers after they seized power. (Those attacks included the famous burning of books on the Opernplatz; Toller’s books were burned that night.)

Hotel Mayflower put Ilse in Dubrovnik in 1933. Now I had evidence that she was there in that moment.

The 1939 file had two fascinating documents: a letter written by Toller to an editor at Random House on Ilse’s behalf on February 13, seeking a job for her, and an almost immediate reply in the negative.

My guess had been that Toller did not want to hire Ilse as his secretary. His own finances — as well as his physical and mental state — already were in disrepair in early 1939. The opening of the play depends on this friction. A tug of war. And here it was in black and white.

I was ecstatic when I left John Spalek’s house. I had gotten so much right in my early drafts. But it was Ilse’s letter to Spalek that I reread over and over again.

The charge of holding something Ilse had typed and signed lingered with me. But as read the letter more closely, her curt hedging and intriguing half answers amidst astonishing new leads and bits of information stuck out. There was a veiled contempt for Toller as well.

Amidst her sharp and succinct recall of vivid details, Ilse complained that “[i]t is long ago now and has become very vague in my mind.” And she added: “I am sorry I c&n’t [sic] be of more help…” (That “&” — and her half-hearted attempt to correct — it seems to indicate a letter typed in haste.)

Suddenly, an even more “complicated” Ilse began to flow into my characterization. This strengthened Hotel Mayflower immeasurably.

I could sense the enormous depths of feeling lurking under her terse letter to Spalek. Mingled emotions and evasions. A complicated woman who saved herself by any means necessary from the catastrophe engulfing Europe.

A woman who should be at the center of a play.

(Images: The images of Ilse Burroughs that accompany this story have been digitally enhanced for greater clarity by Stage Write. The original images are U.S. government records obtained via a request to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.)

Fascinating. Two of my radio plays were cared from documents written by the plays' central characters. A very special relationship grows as tge wirk continues.