In my play, An Evening with Lola Montez, the greatest celebrity of the mid-19th Century offers the audience a succinct account of her fractious years in Munich, which ended with the abdication of King Ludwig I in the tumult of 1848. There are lies of commission and omission aplenty in Lola’s version, as well as a healthy dose of righteous indignation and self-justification:

Did Lola Montez meddle in Bavarian politics? Bah! She improved them!

Yet, as with anything involving Lola Montez, there is truth amidst all the inventions. She did become a powerful force against the retrograde politics of Bavaria — both as an emblem and in practical terms. Indeed, as she mentions in the play, Munich was the only site of revolution in 1848 where reaction ruled the day:

All over Europe in eighteen forty-eight, nations rose up in favor of reforms and freedom. But what did the agitators of Munich want? Cheap beer.

(LOLA goes to the water glass and drinks.)

And the expulsion of Lola Montez from Bavaria.

What really happened in Munich? The story is long and tangled. It took Bruce Seymour nearly two-fifths of his essential biography — Lola Montez: A Life — to sort through it.

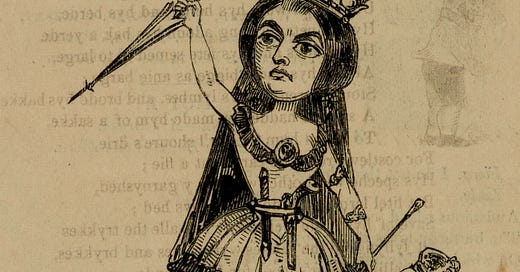

Some basic facts are clear. King Ludwig I became besotted with Lola Montez. She became a royal favorite — and even secured a noble title as the “Countess of Landsfeld” despite the determined efforts of court functionaries to prevent it.

Lola also undoubtedly became willingly entangled in political and sexual intrigues in the capital. And most important: Her undeniable influence on Ludwig led her to become a symbol that attracted the anger and violence of reactionary mobs who compelled the king at last to abdicate in favor of his son on March 20, 1848.

A few key questions about Lola’s time in Munich were at the center of my mind as I tried to telescope a complicated timeline into a one-woman show.

What was Lola Montez’s actual relationship with Ludwig?

The most notorious story about Lola and Ludwig is one that was often recited about their first audience. The king was supposed to have asked if the dancer’s bosom was “nature or art.” Her reply was to cut open her dress and show him.

This story is certainly false. And it demonstrates the intensity of the salacious slurs that were heaped upon Lola Montez by the citizens of Munich.

Questions remain about the exact details of the sexual affair between the king and the dancer, yet the intensity of their connection is undisputed. It is confirmed readily by existing documents, as well as Ludwig’s outsized public gestures of favor. Lola’s portrait was installed in his royal “Hall of Beauties.” He wrote her terrible poetry in Spanish. And he made her countess on August 25, 1847 —despite immense intrigues against her ennoblement within his own court.

Indeed, Ludwig’s ferocious drive to elevate and lionize Lola Montez was intensified and accelerated by his own sense that his royal prerogatives were being frustrated and his favorite was being abused by his own subjects. Having decided that “my Lolitta” was under his protection and extensive patronage, he reasoned, subjects and court must bow to his desires.

Resistance was futile. Until it wasn’t.

Lola Montez certainly took advantage of this seeming aura of inviolability. Far from retiring from the scene to enjoy the favors granted by Ludwig quietly, she flung herself recklessly into the messy politics of Bavaria. She even conducted affairs with some of her key supporters, most notably Elias Peissner—the head of the claque of Munich students who became her most fervent and vitriolic supporters. (Peissner was later exiled and moved to the United States, where he became a professor of German at Union College and died leading Union troops at the Battle of Chancellorsville.)

How did Lola Montez’s house on Barer Strasse 7 come under siege?

Today, the small “palace” that Ludwig I bought for Lola Montez at Barer Strasse 7 near the Karolinenplatz has vanished. But in 1847 and 1848, it became the site of pitched battles and violent mob attacks.

In An Evening with Lola Montez, I have telescoped a number of these incidents into one episode, focused on the most dramatic and final attack on February 11, 1848 — the night when she was formally (yet not entirely successfully) ousted from Munich.

As the fever of resentment toward Lola Montez in the city’s streets rose to a level that was impossible to contain, the dancer’s house was already under attack the day before on February 10 — and negotiations were underway for her to depart.

Yet Lola being Lola, she opted for a response to the mob that aligned tightly with her own aggrievement. Indeed, her anger combined with her decided flair for the dramatic to thrust her boldly into harm’s way.

As Seymour records in his biography, a carnival of bloodlust had progressed to attackers tossing stones and trying to scale the palace walls when Lola finally took action:

Suddenly, to everyone’s astonishment, Lola swept out of the house with a pistol in her hand, planted her feet on a small rise in the garden, and shouted in broken German to the mob streaming over the wall, “Here I am! Kill me if you dare!” Frozen for a moment by her wild challenge, the mob watched Lola rage at them, and then the shower of stones was directed at her. “If you want to kill me, here’s where you have to hit!” and she pointed to her heart. It was too much for her friends and servants, who rushed out to overpower her and drag her, screaming and kicking, back into the house.

A carriage was prepared and Lola fled at last. She would return to Munich later under dangerous and dubious circumstances before finally being ejected from Bavaria. But she never returned to her home in Barer Strasse 7 again.

Did Lola Montez star — as herself — in a play about the tumultuous days of 1848?

Yes. And it is perhaps one of the most fascinating and interesting parts of this tale.

There is no extant version of the script for a play called Lola Montez in Bavaria. This isn’t unusual. As I noted a few years ago in an essay about Our American Cousin (the play that was unfolding as President Abraham Lincoln was shot in Ford’s Theatre in Washington DC in 1865), a curious and fortuitous accident is the only reason that an earlier version of the script was saved.

So we don’t have the script of Lola Montez in Bavaria. But we do know that in 1852 in New York City, she made her debut as an actress in the world premiere of this “ripped from the headlines” five-act drama about her misadventures in Munich. An advertisement for the play in Australian archives lays out a narrative the hews closely to actual events.

Era the First—Lola Montes—The Danseuse

Era the Second—Lola Montes—The Countess

Era the Third—Lola Montes—The Politician

Era the Fourth—Lola Montes—The Revolutionist

Era the Fifth—Lola Montes—The Fugitive

Despite some poor notices of the play as an artistic endeavor, Lola Montez in Bavaria appears to have been a smash. One can only imagine how thrilling (and novel) it was for an audience to see a personage involved in such notable events acting them out upon the stage.

As I pondered how I would approach writing An Evening with Lola Montez, the sensation that she must have felt playing herself — as a character — gnawed persistently at me. As I have written previously, Lola Montez gave her autobiographical lectures a few years later (in the later 1850s) as a person “close to” Lola Montez. The notion of the distance between person and character is quite explicit.

I wonder still what effect a few years of playing oneself on the stage might have had in shaping precisely how a woman born in Ireland in 1821 as Eliza Gilbert might portray herself to the audiences for her lectures.

It is a question which is essential to my own play. Indeed, it is also a key to approaching the extraordinary life of Lola Montez. She was a woman who succeeded against long odds — not only to survive, but also to carve out a place for herself as an independent woman in an era when this was almost impossible.

Yet at what price? There is conflicting evidence from Lola’s final years. She appears to have slipped in and out of this character she had created to survive in the early 1840s until her death in 1861.

Allowing Lola Montez (and Eliza Gilbert) to speak for themselves is the engine driving An Evening with Lola Montez. Her authentic voice deserves to be heard and remembered.